Suchen und Finden

Service

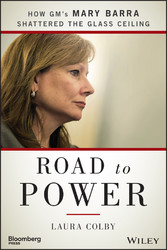

Road to Power - How GM's Mary Barra Shattered the Glass Ceiling

Laura Colby

Verlag Bloomberg Press, 2015

ISBN 9781118972656 , 192 Seiten

Format ePUB

Kopierschutz DRM

Preface

Just don't go there.”

That was Mary Barra's advice when, in March 2012, she was asked at a meeting of Michigan's women in business organization, Inforum,1 about whether she had experienced discrimination as a female manager during her career. Hard as that is to believe—coming from a rare woman engineer, who started on a factory floor at the age of 18 back in the early 1980s—Barra denied ever being held back by being female. “I never said, ‘that happened to me because I’m a woman.'”

Like many women of her generation, Barra played down gender as her career advanced. And she rose through the ranks of General Motors, a company that caught on early to the idea that women make up not only a large portion of the potential workforce, but also a huge share of potential customers. Encouraging women to become leaders made business sense, executives told me over and over again, because women represent a large proportion of car buyers. GM's moves to include women didn't come in a vacuum, though: They followed a string of U.S. government actions that made the company take notice—including a discrimination lawsuit.

Pushed or not, GM has been more successful than most large companies at cultivating high-ranking women, especially starting with Barra's generation. Though the numbers of women on the board and in management still lag behind men, they are at least twice the average of other large publicly traded companies that make up the Standard & Poor's 500 index. Some 26 percent, or six of the 23 top corporate officers are women, and there's a cadre of female vice presidents behind them. That compares with 8 percent for the S&P 500 index companies.2 There are four women on the company's 12-member board of directors, or 33 percent, versus an average of 18 percent for other S&P 500 companies.

GM, especially in 2014 after it was disclosed to have failed to recall millions of cars that had a potentially deadly defect for more than a decade, has been criticized time and again for its bureaucratic culture, where a focus on process can supersede common sense. Yet in reporting this book, one thing that has struck me is that the same obsession with systems and processes has had a big role in creating a cadre of women, including Barra, who are just now getting to the top.

GM executives began reaching out to women as early as the 1970s, as the women's liberation movement was changing the way workforces operated. The steps accelerated and became more concrete following the company's 1983 settlement of a decade-old employment discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Under the landmark deal, reached while Mary Barra was a college student at what was then the General Motors Institute, GM agreed to set goals for the promotion of women and minorities and to report back to the EEOC on its progress. Managers were asked regularly where the women in their areas were, and were encouraged to seek out female talent.

Throughout her career, Barra had mentors both male and female who tried to make sure she got opportunities to grow and advance. Once she was designated a high-potential employee, she was rotated through different positions in the company, at times well beyond her comfort and skill level. By embracing those new challenges, Barra deepened her knowledge and skills and was able to become a better manager. She in turn helped other women, both informally and formally, including setting up an internal networking group for women at the company in the 1990s.

Barra went through a decades-long grooming process before ascending to the top. One of the most striking things about her career is how close she was to some of the most important inflection points in the company's history. Like an automotive Forrest Gump—but smarter—she was often just below the radar, not yet powerful enough to get noticed by outsiders. Still, she was there, soaking up knowledge, learning lessons from the company's successes and failures, and building a network of mentors and supporters.

Her first job out of college in the 1980s was at a factory that was one of the first North American plants to adopt Japanese manufacturing and management methods—which Barra would be instrumental in applying across the company years later. The experiment failed after its cars had safety issues, in a foreshadowing of a safety crisis Barra would face decades later as the company's chief. In the 1990s, when CEO John Francis “Jack” Smith Jr. tried to bring order and logic to GM's sprawling and bureaucratic culture, Barra was in the executive suite, working as his personal assistant. When the company was sliding toward bankruptcy, Barra was one of the top managers scrambling to invent a recovery plan. Following the government bailout, it was Barra who fought to keep executives' pay from being sliced and who helped build the new management team. As the company revamped its car models postbankruptcy, she was in charge of the effort. It was only after decades of steadily climbing the ranks and proving herself time and again that she finally won a job in the public eye.

Loath as she is to play the gender card, Barra had little choice but to “go there” once she was named chief executive officer of General Motors in December 2013. Hers is the highest position ever held by a woman at a global automaker and, given GM's size and importance to the country's economy, perhaps the most important corporate position ever held by a woman in the United States. Much was made of her gender in the news reports of her appointment. Media outlets, including Bloomberg News and Bloomberg Businessweek, which put her on its cover, wrote profiles. When attending the Detroit Auto Show in January 2014, just as she was taking on her new role, she was mobbed like a rock star.

Amid all the celebration, there was an undertone of condescension toward this woman with an electrical engineering degree, an MBA from Stanford, and more than 30 years of increasingly responsible positions at GM. Even the man who promoted Barra, her predecessor Dan Akerson, said that seeing her take the CEO role was “almost like watching your daughter graduate from college.” Barra's pay was found to be less than Akerson's, until deferred compensation and stock were taken into account.

Little did she know then that within weeks that aura would be tarnished and she would face the greatest challenge of her career. The company had delayed for more than a decade recalling cars for a safety defect that has cost at least 45 customers their lives, a tragedy whose full scope is still being determined. GM—and Barra—were vilified in the Congress that had approved bailing out the bankrupt company only a few years earlier. There, too, gender became an issue. Some pundits even posited that Barra had been given the CEO role by Akerson only because she was female. They argued that she would present the company with a softer image and one that critics were less likely to attack.

Anyone who watched her interrogation in front of the House of Representatives and Senate panels investigating the ignition switch recall—where, ironically, many of the most hostile questioners were women—would reject the argument that she got a pass because she is female. “I am very disappointed, really, as a woman to woman,” scolded Senator Barbara Boxer when Barra was unable to answer detailed questions about the recall during the first round of appearances in April.

There was also some friendly fire. In a national televised interview on NBC's Today show, Matt Lauer asked Barra whether she thought she could be both a “good mom” and CEO of the largest U.S. automaker,3 a line of questioning that immediately drew criticism for its perceived sexism.4 While Lauer responded that he would ask a male CEO a similar question, he gave no examples of having done so.

Of those who know Barra, who have followed her career, and who are familiar with the challenges facing the auto industry, rare is the person who argues that she is unqualified to lead GM. Most would say she got the job despite being a woman, rather than because of it. She has proved herself over decades, starting when she joined Pontiac as an 18-year-old cooperative education student. Along the way, she expanded her skills, made some smart decisions, formed key alliances, proved her intelligence, and did a lot of hard work.

In reporting this book, I learned that Barra, while exceptional, is not an outlier.

She is one of a cadre of women rising through the famously bureaucratic corridors of power at GM and who are just coming into their own. Many of them are engineers who were fearless about following their interests into areas where women were far fewer than they are today, while others are working in finance, marketing, and general management areas. Still, even with corporate programs that seek them out and aim to advance them, women remain underrepresented across the auto industry, including at GM.

This book aims to illuminate the steps Barra took in her career and, in so doing, to provide ideas for others to follow, whether they are aspiring engineers or accountants, parents of girls, teachers, or human resources executives at companies that want to stop shortchanging half of the population—and half their potential customers.

Barra...