Suchen und Finden

Service

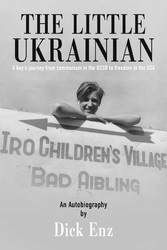

The Little Ukrainian

Dick Enz

Verlag BookBaby, 2019

ISBN 9781543956979 , 252 Seiten

Format ePUB

Kopierschutz frei

Chapter 1

Life Where I Was Born

Suddenly, it happened. I began to perceive the world around me, even though my world at that time was very limited. I began to remember things, but only certain events, people, and places made a lasting impression. For instance, the time I fell into the water hole and almost drowned. I don’t remember how long I was in the water, but it must have been a long time, because my father, who pulled me out, had run across a field of about a hundred yards. That always puzzled me. How had he known? How had he got there so fast?

There were other events. Some I remembered but didn’t understand. Among these were my grandmother dying, a brother being born, then another brother being born while my mother was dying. I also remember the tanks rolling on our primitive roads and almost being run over by them, sleeping in underground shelters, and going to live with Uncle Joseph and Aunt Theodora.

My name is Wladyslaw Strzelecki, although I always preferred the short version of my first name, Wlady (pronounced like laddy to rhyme with daddy). According to Aunt Theodora, I was born on April 16, 1935, in a settlement of scattered shacks called Josefofka. As far as I know, there was neither birth certificate nor other papers to document the event. Josefofka was probably never on any official map. It was somewhere between Kiev and Rovno. At one time, it may have belonged to Poland, but at the time of my birth, it was part of the Ukraine and the Soviet Union or Russia.

My mother was Ukrainian; my father was Polish. When I began to remember things,

I had two older brothers: Dezik, several years older, and Adam, a year or so older. There was a baby sister called Janka, and my paternal grandmother lived with us. In addition, there were several relatives living nearby. Father’s sister, whose husband had died, lived across the field west of us. A footpath across the field connected our two shacks. On the other side, about half a mile east of us, lived another aunt and uncle. They must have been well-off, because they never seemed to need anything. They had no children. About two miles northeast of us lived another aunt and uncle. This was Uncle Joseph and Aunt Theodora. They were the wealthiest of all my relatives. At one time, they had children, but apparently they’d died in infancy, so my aunt and uncle were left childless.

The circle in the top left corner of this map is the area of Ukraine I think I was born in. The nearest city to this area was Korets. About forty miles west of this city was Rovno, now called Rivne.

All the people in this settlement made their living from the land. Some had more land, better land, more horses, more cows, more pigs, more chickens, or more of everything else. Others had less. Of those that had less, my aunt across the field and my family had the least. In my aunt’s case, the poverty was attributable to her being a widow. She had plenty of land, but most of it lay fallow as there was nobody to work it. She also had four children—two boys and two girls. In ages, the children corresponded to those in my family—the girls being the oldest and youngest, with the boys in the middle. The boy corresponding to my age was named Broniak and was my closest playmate.

No such excuse can be made for the poverty of my family, but we certainly were poor. In fact, the shack where we lived was the worst in the whole settlement. Even my aunt across the field had a better house, for at least the living quarters and the barn were different buildings. In our case, it was all one building. It was comprised of the north end as the living quarters, the middle was where the horse and cow were kept, and the south end was where the grain and hay were stored. On the west side of the south end was an annex for the pig, when there was one. Above the pigpen was the chicken coop. On the east side of the south end was the outhouse, which consisted of a hole in the ground. The south end of the building was constructed with thin boards; the other parts were made with small lumber. To make the structure airtight, the cracks were plastered over inside and outside with clay. The roof was made of straw.

There was a hall between the living quarters and the stable. There was only one entrance to the living quarters, and that was through this hall. The living area consisted of one big room. The floor was hard-packed dirt; the walls and ceiling were whitewashed clay plaster. There were two windows: one faced west, the other north. As one entered the room, the water-bucket stand was on the left, and a large wood burning oven was on the right. This oven was constructed of bricks and clay. It was constructed as a large, half-cylindrical cavity, flat on the bottom, curved on the sides and top, about three feet wide, two feet high, and eight feet deep. The whole structure sat about three feet off the ground. The chimney was built in front of and above the cavity. On the other side of the chimney and atop the oven was a flat space. This was where Adam and I slept.

The oven operated in the following manner. A fire would be lit as far inside as possible. Kindling would be added, followed by larger and larger logs. The draft of the chimney would carry the smoke up and out of the house. Sometimes there was no draft, and the smoke would fill the house instead. When the logs were sufficiently burned, cooking was done by just shoving the pots in to the coals; baking entailed raking the coals toward the front and placing the loaves beyond the coals into the cavity. Often, the bread crust contained pieces of charcoal, but with the scarcity of bread, we ate it just the same.

Proceeding farther into the room, on the right was a wood burning stove, again, constructed of bricks and clay with an iron plate on top. The plate had two holes, covered with concentric rings that decreased in size. To cook on the stove, the required number of rings were removed from a hole and replaced with a like-sized pot. Normally, the oven was lit in the morning and the stove at night. Their function was not only to prepare the respective meals but also to warm the house, as there was no other heat source.

Behind the stove was a large wooden chest that normally contained flour, if there was any. It also served as Dezik’s bed. In the northeast corner of the house stood the bed where my parents slept. Its mattress consisted of straw covered with a homespun blanket. The cover was provided by a quilt made from rags. In front of the bed was the cradle, a wicker basket suspended from the ceiling by four ropes. Ahead of the cradle, to the left of the bed was a chest. It was my mother’s proudest possession: her hope chest. It contained all her valuables, like some clothes, candles, and cherry- or strawberry-flavored vodka to be used as medicines. A table was to the left of the chest, under the north window. To its left, along the west wall, was another bed, where Grandmother slept.

Such was the situation when I became aware of my surroundings and when memorable events began to happen.

The first of these involved my grandmother. One summer day, I was told that she was ill and that I should stay out of the house. Next, I saw lots of strange people arriving. Then I was told that she’d died and that I should come in and see her. I went into the house, and there she was—pale and motionless, dressed in her best clothes, lying on her bed. Soon, some men came and brought a big pine box.

When I saw Grandma again, she was lying in the pine box, and I was told to kiss her, as this would be the last time I’d ever see her again. Immediately afterward, the men placed the cover on the box and nailed it shut. One man took a pencil and a ruler and drew a cross atop the box. The men then took the box, loaded it on a wagon, and drove away.

The next time I was told to avoid the house involved my mother; she seemed sick. My aunt hurried across the field, and there was lots of activity. When it was all over, I was told the stork had brought me a little brother. He was named Edzu, and he displaced Janka in the cradle. Since Dezik now slept in Grandmother’s bed, Janka was made to sleep on top of the flour chest.

There were also happy events, like the time Adam and I were to receive new suits. There was no money to buy clothes, so they had to be made. The making of clothes began with planting flax, harvesting it, processing it into fiber, spinning the fiber into yarn, weaving the yarn into cloth, bleaching and dyeing the cloth, and finally, sewing the cloth into a suit. The process took over a year.

Mother did everything except the weaving and sewing, as she had no loom and no sewing machine. She somehow had the yarn woven and persuaded a lady to sew the two suits. Consequently, one spring Sunday, Adam and I wore brand-new suits, consisting of shorts and jackets. The suits were all we wore, as we had no underwear, socks, or shoes. Still, we were happy to have new suits.

Again, one summer day, I was told to keep out of the house, as Mother was ill. And again, my aunt hurried across the field, and other people came too, including a man who was a doctor. I didn’t understand what was happening, but I was suspicious because people were whispering. Father didn’t look happy, either. It was a scary situation that continued until nightfall.

Finally, since I was with Broniak, my aunt from across the field told me what had...