Suchen und Finden

Service

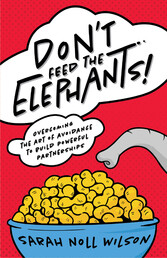

Don't Feed the Elephants! - Overcoming the Art of Avoidance to Build Powerful Partnerships

Sarah Noll Wilson

Verlag Lioncrest Publishing, 2022

ISBN 9781544524498 , 294 Seiten

Format ePUB

Kopierschutz frei

Mehr zum Inhalt

Don't Feed the Elephants! - Overcoming the Art of Avoidance to Build Powerful Partnerships

Introduction

Of course, you know what an elephant is. Big, gray beast, long trunk, and large ears. They like peanuts, have a reputation for not forgetting anything and being afraid of mice.

To be clear, no one wants those real-life pachyderms to go unfed.

There’s another kind of elephant that you’re probably aware of too. It looks like avoidance of addressing a known conflict that creates a harmful barrier to success. It’s big. It’s there. It might be hanging out in the conference room under someone’s chair, or even sprawled across the table. Everyone is aware of this elephant in the room, and no one’s talking about it.

In fact, no one on your team is talking much at all. At least not about anything that matters. Your team is discouraged, disconnected, and disenchanted. No one challenges ideas to get to better solutions or discusses the difficulties they encounter on a project. They all say everything is fine…until it isn’t, and you’re stuck trying to solve problems that could have been avoided with better communication. Your most productive team lead gave notice last week. You’re finding it hard to drag yourself into work in the morning. Something is getting in the way of your team’s success, and it feels like everyone is spinning and getting nowhere. You’d fix it if you could, but you have no idea how to begin. I get it. I’ve been there too. Now, I coach executives and teams through these issues, and I’m here to help you too.

A Reformed Avoider

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been passionate about solving problems and disrupting the status quo. I was especially fearless when it came to rules or expectations from authority that felt limiting. I was only ten years old when I was told that girls couldn’t serve in the church as altar boys. I kept asking, “Why not?” and volunteering, never getting a chance or a reasonable explanation, until one fateful day when a fellow altar boy didn’t show up. I was there with my robes on, ready to step in with a smile. Still one of my (and my parents’) proudest moments growing up.

While I had many moments of speaking up and pushing against the boundaries of authority, that same courage didn’t extend to my personal relationships. It’s much easier to have courage when you have nothing to lose, but when it came to my most precious connections, I was a masterful avoider and smoother-over.*

*Smoother-over, by the way, is a very technical term for someone who works hard to remove the discomfort in a situation by any means possible while not solving the issue at hand.

The impact of my avoidance was put on full display when I started dating Nick, the man who eventually became my husband. Before my relationship with Nick began, my avoidant tactics served to protect me and didn’t impact others (or so I thought), but after meeting Nick, I learned that you can’t hide in relationships. If you try to hide, you won’t just avoid the conflict; you’ll avoid trust and connection as well.

Nick and I had a consistent point of disagreement around how we spent time in our social lives. I resisted talking about it by employing my masterful avoidance skills. I would use classic moves like changing the subject (“What did the Royals do today?”), closing the door, (“I’m too tired to talk right now”), or surrendering, (“Sure, whatever sounds good to you”). But most often, my default was the worst move of them all, pretending nothing was wrong, (“No, I’m fine. Really, I’m FINE!”).

Nick is more introverted than I am and prefers to spend time at home. I was (and still am) very social and liked going out with friends. It seemed to me that Nick never wanted to go out and I always wanted to go out. At that point in my life, I was unskilled in advocating for myself, and it never occurred to me that I could go out without him. My idea of being a couple meant doing everything together. When Nick declined plans, it felt as if I’d been sentenced to staying home, but I worried that calling out this difference in how we wanted to spend our time would damage our relationship. Instead of having a discussion about it, I nurtured the situation into a greater problem through avoidance, eventually growing resentful and bitter about all the activities I believed Nick was making me miss.

One night, soon after we began living together, my team had plans to go out after work. I asked Nick if he wanted to go. He told me he wasn’t in the mood to go out with my colleagues. In all the time I’d spent building a wall of resentment around this issue, I’d become convinced that if I went without him, Nick would be upset about being left at home alone. In my mind, I’d just committed to living with someone who never wanted to go anywhere, which made me feel like I was committing to never going anywhere. I felt trapped.

“Fine,” I said. Inside, I seethed. At twenty-five years old, my emotional regulation wasn’t quite mature at that point. The anger from all the times I’d missed out on something I wanted to do began bubbling up. My flight response kicked into action, and I desperately wanted to remove myself from the situation to avoid conflict. I felt like I needed to get as far away from Nick as I could before I exploded.

“That’s fine. I’m going to bed,” I said, retreating. Of course, at that point, I was so wound up that the way I said “fine,” made it perfectly clear that I wasn’t fine.

Nick gave me a few moments to cool off, but then he came in and sat on the edge of the bed.

“Yeah, we can’t do that,” he said.

“I’m really tired,” I told him, pulling the covers over my head.

“No, we need to talk about it. In this house we talk things through.”

Oh, he was so right. And of course, when you’re angry with someone, you don’t want them to be right. I was trapped under the covers in a state of cognitive dissonance. I loved him, and I wanted our relationship to work, but having that conversation required vulnerability and swallowing my ego. I had to let go of all the self-righteous feelings that come with anger, and I had to admit that I felt differently than he did about going out.

I also knew that Nick was worth the discomfort of tackling this difficult conversation head- on. I pulled the blankets down under my chin, took a deep breath, and started to share how I felt and what I was struggling with.

Nick did the same.

A funny thing happened. While I had always feared that sharing how I felt would make a conflict worse, as Nick and I talked, we actually worked through the tension. Nick explained that he just doesn’t enjoy going out in large groups with people he doesn’t know well. He also told me that he didn’t mind if I went out without him. He wouldn’t feel left behind. Instead, he’d be happy to see me happy and also feel like I was sparing him an uncomfortable situation.

Since we were able to talk about it, over time, we worked out ways to enjoy social time together with friends at home or in small groups, and I learned to feel comfortable going out on my own. Even still, all these years later, when I go out with friends, Nick makes a point to say, “Have fun! Enjoy your time!” to remind me that he’s happy for me to go out and have a good time with friends.

As discussion became our practice, we noticed that every time we had a conversation to work through a tension point, we became closer. Often it isn’t the tension that creates the distance, but the toleration of that tension.

My journey of conflict avoidance recovery continued as I entered the workforce and began to witness firsthand the impact that conversations around conflict had, not only on the success of the team as a whole, but on the team members personally.

Learning Leadership

My first exposure to formal leadership development came when I had a summer job as a camp director and ropes course facilitator. I was a nineteen-year-old theatre major, leading groups of executives through various obstacles where communication and trust were key to successful completion. I worked with teams who not only excelled, but were also energized by the challenges. I also witnessed group situations where contempt hung in the air, choking everyone like bad perfume. I observed all the eye rolling, cutting sarcasm, blaming, and disconnecting that happen when a team’s culture turns toxic.

After graduating with a degree in theatre performance and theatre education from the University of Northern Iowa, I applied for my first office job. Like any good person living in Des Moines, my first office job was in insurance. To say I was a square peg in a round insurance industry hole is an understatement.

During my interview, the hiring managers asked if I thought I could sit still in a cubicle. I told them I didn’t know, but I was ready to find out!

I was not particularly interested in insurance. Mostly, I wanted to have good benefits and my nights free for theatre rehearsals. However, it was at this company that I discovered my love of training and directly learned the massive impact a leader could have on how someone saw themselves.

During this time, I went back to school and got my master’s degree in leadership development at Drake University. Through my graduate studies, I truly fell in love with the philosophy and practices of Adaptive Leadership, a leadership framework developed by Harvard professors Ronald Heifetz, Alexander Grashow, and Marty Linsky that “helps individuals and organizations adapt and thrive in challenging environments.” Through their work, I was introduced not only to the idea...