Suchen und Finden

Service

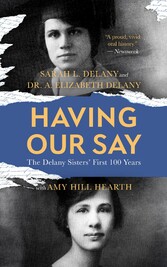

Having Our Say - The Delaney Sisters' First 100 Years

Sarah L. Delany, A. Elizabeth Delany

Verlag Blackstone Publishing, 2023

ISBN 9798212171281 , 100 Seiten

Format ePUB

Kopierschutz Wasserzeichen

6

SADIE AND BESSIE

Our Mama's People

Miss Logan, who would one day be our Mama, was born in Virginia in a community called Yak, seven miles outside Danville. Today, they call it Mountain Hill. Guess they think that sounds better than Yak.

Miss Nanny Logan was a feisty thing, a trait which she could have gotten from either of her parents. Her father, James Miliam, was 100 percent white, and the meanest-looking man in Pittsylvania County, Virginia. Because he was white, he could not legally marry his ladylove, Nanny's mother, an issue-free Negro named Martha Logan.

This is what we were told by our Mama: A fellow named John Logan, who was white, was an army officer called away to fight during the War of 1812. While he was gone, his wife took up with a Negro slave on their plantation. She was already the mother of seven daughters by her husband, and her romance with the slave produced two more daughters. When the husband returned, he forgave his wife — forgave her! — and adopted the two mulatto girls as his own. They even took his last name, Logan. No one remembers what happened to the slave, except he must've left town in a big hurry. This slave and this white woman were our great-great-grandparents.

The two little mulatto girls, Patricia and Eliza, were just part of the family. The only time anyone has heard tell of their older, white half sisters mistreating them was when those white girls were old enough to start courting and they used to hide their little, colored half-sisters! One time, they hid them in a hogshead barrel and after their gentlemen callers left, they couldn't get them out! Patricia was entirely stuck, and they had to use an ax on that old barrel to get her out. Well, they slipped and cut Patricia's leg, and she carried that scar on her knee to the grave.

When Patricia grew up, she had ten children. One thing we remember about her was that one of her babies was born on the side of the road. She would walk to the mill to get her corn ground, carrying this big sack on her head. On the way back one day, she went into labor and could not get home in time. So she had that baby on the side of the road, by herself! And afterward, she just put that baby under her arm, and that sack of cornmeal back on her head, and walked on home.

Patricia's sister, Eliza, meantime, had become involved with a white man named Jordan Motley. They had a child — Martha Louise Logan, our grandma, born in 1842. Eliza had three other daughters: Blanche, LaTisha, and Narcissa, who was the prettiest one of the four girls but never married. Whether those three girls all had the same Pa, we do not know.

They were charmers, all four of those girls, and very popular, but it's said they squabbled quite a bit. Why, our Mama remembered as a little child throwing salt in the fire to put out their fussing. People in those days thought that would stop an argument. Well, Mama said she must've thrown a peck of salt in the fire, trying to put out the fussing between her mother and her mother's three sisters!

One thing's for sure: Those four girls were all only one-quarter Negro, but in the eyes of the world they were colored. It only took one drop of Negro blood for a person to be considered "colored." So Martha Logan and her sisters were in a bind when it came to marrying. If they wanted to marry a colored man, well, most of them were slaves. And they couldn't marry white, because it was illegal for Negroes and whites to marry in Virginia at that time, and for many years after — until 1967! Well, it didn't stop them from having love relationships. Martha Logan took up with a man named James Miliam, who was as white as he could be. We remember our grandparents well because we used to go visit every summer, and we were young women when they died.

One time, James and Grandma had a big fuss, and to this day we don't know what it was about. We think it had to do with race, that he made some remark about little nigger children or the like, because all of a sudden Grandma said, "He's not your Pa, or your Grandpa." From then on she told us we were to call him "Mr. Miliam." Yet we all just went on as before.

Mr. Miliam built a log cabin for Grandma a few hundred feet from his clapboard house, on the sixty-eight acres he owned in Yak. He even built a walkway between the two houses so he could go see Grandma without getting his boots muddy. Now, this kind of arrangement was unusual between a white man and a colored woman. More common was when a white man had a white wife and a colored mistress on the side. But James Miliam had no white wife, and was entirely devoted to Grandma. They weren't legally married but they lived like man and wife for fifty years and didn't part until death.

They clearly loved each other very much. If anyone was bothered by this relationship, they kept it to themselves. That's because Mr. Miliam was one tough fella, and that's no lie. He was about six feet, four inches at a time when most men were about a foot shorter. When he was a very young man, he had a job rolling huge hogsheads full of tobacco from the countryside to Richmond. Usually, it took two men to roll the barrel. But James Miliam could roll one by himself. All of his adult life, he carried a pistol in a shoulder holster, for all the world to see. He was a mean-looking dude.

That was a time when a colored woman wasn't safe in the least. Men could do anything to a colored woman and they wouldn't get in trouble with the law, not one bit. Well, James Miliam let the word out that if anyone messed with his ladylove, why, he'd track 'em down and blow their head off, and everyone in Pittsylvania County knew he meant it. So, Grandma could come and go as she pleased and no man, colored or white, would tangle with her. No, sir!

Every Sunday, Grandma would walk to the White Rock Baptist Church for services. One time, there was a movement in the church to throw her out, on account of her relationship with Mr. Miliam. But one of the deacons stood up and defended her. He reminded the congregation that those two would have been legally married if they could. And that those two were committed to each other, much more so than some of those in the church that were legally married! And anyway, James Miliam couldn't help being white. So, they let Grandma keep coming to that church.

Mr. Miliam was a farmer, and grew tobacco and everything else you can think of on his land. But he also served as a "dentist." Of course he had no training. It's just that he owned the right tools and was willing to pull teeth. Mr. Miliam would get the two biggest men he could find to hold down the patient, and then he'd yank that old tooth right out. Folks said you wouldn't go to Mr. Miliam unless your tooth ached so bad you wished you were dead anyway.

Another thing: Mr. Miliam was a root doctor. He was always messing around with different herbs and roots and things, looking for cures. As an old man, he got a patent for a cure for scrofula, which was a nasty skin problem that erupted on the necks of folks who had syphilis. Mr. Miliam got $2,500 for the patent. We remember that he went to Richmond to sign the papers, and demanded to be paid in cash. Seems he could not read or write — but he could count cash, yes, sir! He took the train back to Danville, and by then the bank was closed. So he walked the seven miles to Yak with that cash on him, and everybody knew it, too. But nobody bothered him. When he got home, he put that money in a sock and tossed it into the smokehouse, and Grandma said, "What are you doing that for, Jim?" And he said, "Aw, ain't nobody going to bother it. I'll take it to the bank tomorrow." Nobody messed with Mr. Miliam.

Grandma was quite a businesswoman in her own right. She owned her own cow, and although she didn't know it, what she was doing was pasteurizing the milk and cheese. She had somehow discovered that if she scalded her pans with boiling water, the milk and cheese was healthier. She also let the dairy products sit in direct sunlight for a spell. Folks came from all over that part of Virginia to buy Martha Logan's cheese, because it tasted good and lasted longer.

Grandma always had money of her own, and she would give some to us once in a while. She made a garter which she wore on her thigh, and in it she kept five twenty-dollar gold pieces. Grandma always said she liked being able to get her hands on a hundred dollars in a hurry. It was like her social security!

Grandma and Mr. Miliam had two daughters: Eliza, born in 1859 and named after Grandma's mother, and Nanny James, our Mama, born two years later, on June 23, 1861. Mama was named after Mr. Miliam's mother (Nanny) and himself (James). Mr. Miliam's daughters could not carry his last name legally, but he was determined that his name be in there someplace.

Eliza got married young, but Nanny — our Mama — was set on getting an education. She had been inspired, at the little one-room schoolhouse, by a teacher named Miss Fannie Coles. Nanny admired Miss Fannie Coles so much that she would take her own lunch and give it to Miss Coles every day as a gift. Miss Coles had no idea that her student was sacrificing her own meal.

Mama always said she had a sweet childhood there in Yak, carefree and running around the farm, playing with her sister. She was sheltered from the world, though, and when she set her sights on going to Saint Augustine's School in Raleigh, North Carolina, Grandma declared she could not go alone. So when Mama packed her bags, so did Grandma.

The whole time Mama was in college in Raleigh, Grandma was nearby. Grandma was an excellent cook and seamstress and was able to get as much work as she wanted.

Grandma went home to Danville by train as often as she could. When she'd get to the station in Danville, she...